PENNSYLVANIA

Summer 2009

1 of 1

PENNSYLVANIA

Summer 2009

1 of 1

It’s something I have to see for myself, so here I am in Pennsylvania, following Billy’s directions up the steep side

of a mountain.

A week ago he had called me from the same spot, a bit breathless from excitement. After the success of his first

Rattlesnake exploration (see PENNSYLVANIA 2008), Billy scouted another Crotalus horridus location, but this one is

remarkably different.

So now I’m with my friend, Danny, and carefully we work our way up a talus slope, looking for a very specific

rock. It seems almost impossible, there’s so many slabs, each one text-book perfect for Timbers.

Fortunately, as per usual, Billy’s instructions are precise, and finally the particular boulder he told us to watch for

comes into view. But, still, we’re unprepared for what we see.

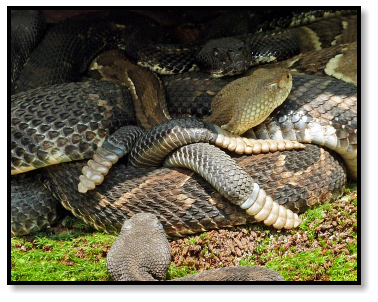

Danny and I stare in disbelief. It’s an image so startling, we have a hard time absorbing it.

What we’re witnessing is a rookery, a concentration of gravid females sharing the same space during gestation.

(Rather than lay eggs, Rattlesnakes incubate their embryos internally, giving birth to live young.) Research suggests

that individuals in such gatherings may be related to each other, raising the interesting possibility of timbers living in

family groups, a social structure generally unknown among snakes. (For more on this subject, read the article Social

Lives of Rattlesnakes.)

Who knows why they chose this singular spot

―

to us humans, the surrounding boulders seem to offer identical

conditions

―

but obviously there’s something special about this rock: repeated trips found the females in exactly the

same place, where they remained throughout the summer.

The initial shock gives way to fascination. The rattlers are totally alert, yet completely calm, getting on with their

day. For the next three hours we simply watch what unfolds before us.

The amazing thing is that the snakes are constantly in motion, the entire mass changing shape every few

minutes. After a while we detect a pattern. Not all of the snakes move at the same time. Every so often some

individuals retreat from the sun deck and join others resting in the shadows beneath an overhang, crawling silently

through a tangle of black and brown bodies, insinuating themselves into the shifting pile.

At the same time, others stir and make their way outside to take their turn at basking. We wonder if it’s a

deliberate rotation; perhaps some form of heat exchange, the mass temperature of the pile adjusted by individuals

recirculating between sun and shade?

The morning heat forces the majority back into a miniature cave, but a few snakes continue to venture back and

forth, always staying within a few feet of the rocky opening and each other.

By mid-day it becomes too hot, and eventually all the snakes disappear deep into the crevices of the cave. We’re

left alone, still feeling a bit dazed.

It’s been an experience unlike any other I’ve ever had herping, beyond memorable. To be so close to so many

Rattlesnakes for so long, watching how they live at home, observing their behavior and wondering what it means, is to

catch a glimpse of the mystery in nature and the curiosity it inspires.

Of course, we don’t want to just contemplate, we also want to play. Enough of these venomous serpents, give us

something we can catch and hold in our hands!

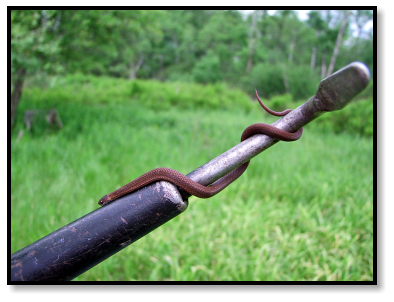

There’s a nearby field with reliable trash, good for Garter Snakes and the occasional Redbelly. Conditioned by

our time with Rattlesnakes, we make sure to use proper equipment before free-handling these wild-caught snakes.

This field was also the unexpected site of a lifer for me. Billy and I are walking through the grass, looking for

boards to flip, when he turns around and spots something at his feet. “There’s a turtle,” he says calmly, assuming it’s a

common Box Turtle, but then he picks it up and exclaims, “It’s a Wood Turtle!” I get even more excited, this being my

first ever in the field.

Having one in hand allows me to truly appreciate the meaning of its scientific name, insculpata, which refers to

the sculptured appearance of the turtle’s shell, complete with chisel marks and carved edges.

Back at the rookery, periodic visits were made to check on the Rattlesnakes, who were always there.

Predictability led to growing anticipation; we knew what was going to happen, and we had a good chance of being

there at the right time.

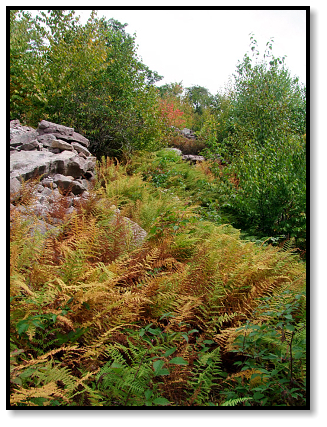

Late in the summer Danny and I return with Billy. It’s a bit cooler than previous trips, and a few leaves are just

beginning to turn.

We arrive at the familiar site and glance around. No snakes at the special rock, it looks deserted. But then, a few

boulders over, we see what we were hoping to find: the rookery has become a nursery.

Gradually we realize there are babies everywhere. Most are hiding in crevices, the neonates being much more

skittish than adults, but if we remain still enough they slowly start to emerge.

It’s even better than I imagined. More than the excitement of seeing so many snakes, there’s something about the

continuity, the connection between knowing the mothers and meeting their offspring. Perhaps it’s that sense of

wonder coming full circle, the culmination of an unforgettable season.

Wood Turtle

Glyptemys insculpta

Redbelly Snake

Storeria occipitomaculata