FLORIDA

October 2006

1 of 3

FLORIDA

October 2006

1 of 3

This trip was inspired by a most excellent book, The Swamp, by Michael Grunwald (no relation). It's an

extremely well-written, well-researched political history of the Everglades, with just the right quotes from horrified

early explorers to tantalize us contrarian herpers:

“It

teemed

with

leeches,

lizards,

and

other

ugly,

slimy

creatures

.

.

.

.

It

is

in

fact

a

most

hideous

region

to

live

in, a perfect paradise for . . . . alligators, serpents, frogs and every other kind of loathsome reptile.”

Jacob Mott, 1836-38 “Journey Into Wilderness”

Sounds like home to me.

In fact, reading the book made me very nostalgic. Growing up in Miami, my happiest and most formative

herping experiences were spent swamp-tromping, and to this day the Everglades/Big Cypress remains my favorite

place on the planet. So I called my brother Ron and proposed a long weekend of camping in the middle of the

Swamp, a few days of immersion back where my herping began.

Driving west on the Tamiami Trail we enter the Everglades and encounter a sign of the times. The same old

tourist sites are still there, but now they feature exotic Burmese Pythons as local Everglades attractions.

To learn more about the introduced invasion, see the Burmese Python page on the website of the Everglades Cooperative

Invasive Species Management Area.

Footnote: The following year we found one of our own.

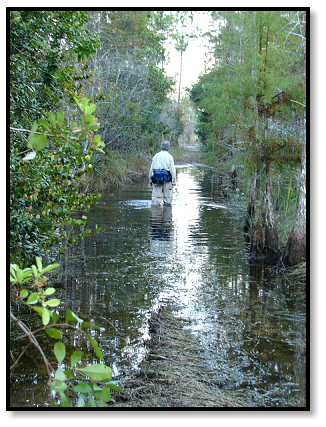

Deeper into the swamp we decide to go off-road. The warm water oozes into my boots as they sink in the

muck, and smiling, I recall the familiar sensation of close contact with the Glades.

As we slog through the slippery marl, countless frogs keep springing out of our way.

.

Following no particular trail, we cut across the sawgrass prairie towards a stand of cypress trees in the distance.

Wherever a depression in the limestone bedrock creates a shallow pond, water-loving cypresses take root in the

peat that accumulates at the bottom. When the trees shed their leaves in winter ― earning the name Bald Cypress ―

the decaying foliage forms a mild acid that further dissolves the limestone and enlarges the depression.

The trees grow tallest in the middle, where the most amount of organic matter settles in the deepest part of the

pond, and their height decreases towards the outside, where less peat accumulates along the shallow edges. This

gives the formation, called a cypress head, its distinctive dome-like appearance.

We slip past the smaller, crowded trees of the periphery and wade into the shadowy stillness of the interior,

surrounded by fluted columns of silver-gray bark and epiphytes. Everything is hushed, like entering a sanctuary.

For me, the quiet center of a cypress head has always been a subtle world of muted colors and intimate

observations. Stare long enough and the eye is rewarded with minute revelations, such as this tree frog (left) blending

gray with the cypress bark instead of its usual green color (compare to the normal phase at right).

Of course, that’s not to say these hideaways lack for charismatic megafauna. Move to the center of a large

cypress strand, where the trees open up and encircle a deepwater pond, and there’s a good chance you’ll encounter the

Swamp’s most famous residents.

Burmese Python

Python molurus bivittatus

Florida Cricket Frog

Acris gryllus

Southern Leopard Frog

Rana utricularia

Pig Frog

Rana gyrlio

Green Tree Frog

Hyla cinerea