COSTA RICA

July 2003

1 of 7

COSTA RICA

July 2003

1 of 7

On our first trip to Costa Rica, in April 2002, my brother Ron and I spent all of our time in the Caribbean versant,

mostly in lowland rainforest. It was the end of the dry season, so we had concentrated on the wetter, eastern side of

the country, where herps were more likely to be active at that time of year.

Our current trip is during the rainy season, so this time we plan to explore the western side, from the steep

jungles of the Osa Peninsula in the south, to the flat dry forests of Guanacaste in the north. New terrain filled with

new species ― we’re looking forward to a lot of first-time finds!

First destination is near Dominical along the coast of the southern Pacific zone. We leave San Jose and drive

south, ascending mountains to cross the Talamanca cordillera. Along the crest it is clear, windy, and surprisingly cold

due to the high elevation. Not very promising conditions for finding reptiles, but we had been advised to keep our

eyes open for sheets of tin scattered by the roadside. These highlands are home to a beautiful species of montane

Alligator Lizard, and in cool temperatures they might be found warming up under pieces of scrap metal exposed to

the sun.

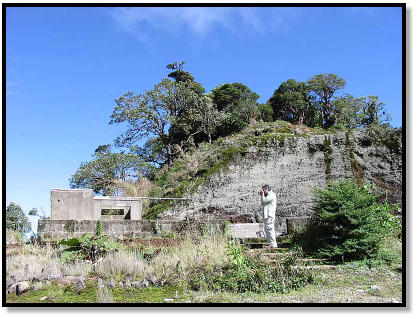

We come upon the ruins of an abandoned building and begin to poke around. I’m having a hard time

reconciling the chill wind with traditional notions of the tropics ― where is the sultry summer promised by July?

Surely no self-respecting heat-loving herp would be out in these conditions.

I go through the motions of turning everything I can, but each unsuccessful flip of cold metal reinforces my

skepticism. I’m preparing to leave when Ron calls out “Got one!” Virtually the last unturned piece of rusty tin, and he

uncovers this variegated jewel.

.

We continue towards the Pacific coast to meet up with Quetzal and Monica, our gracious and accommodating

guides for the week. They're Americans who moved to Costa Rica and built Parque Reptilandia, a very professional

and impressive serpentarium near Dominical, and who also lead rainforest hikes in search of reptiles and amphibians.

Even before construction is completed, the local herps are moving in. Marine Toads wander the grounds at

night, trilling in the dark and feeding beneath the lights, while Red-eyed Tree Frogs establish breeding colonies in the

aquatic enclosures reserved for Caiman and Crocodiles.

That night the four of us go for a hike on some nearby jungle trails. It isn’t raining but the forest is completely

wet from the warm, humid air (now this is the tropics!). Leaves are shiny and slick, and everything (including us) is

dripping with moisture.

First critters we spot are creepy-crawlers like whip scorpions and tarantulas, and giant wasp nests hung hidden

from the rain, plastered on the underside of sheltering leaves.

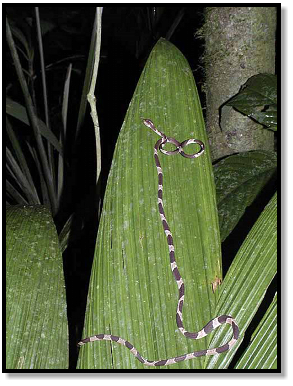

This slender snake is found foraging for lizards that might be sleeping on the fronds and leaves that comprise

the thick layer of understory plants.

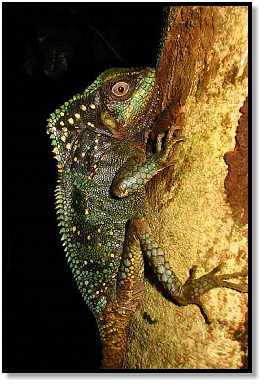

One species we had hoped to find on our last trip, but never did, was the unusually shaped Casque-Headed

Lizard. Consequently, it was high on our target list this time around, so we’re thrilled when Monica cries out,

“Corytophanes!” We run over to where she’s pointing to a light brown lizard with a serrated crest, asleep on a small

tree trunk. Shortly afterwards, another one is spotted, this time larger and more colorful. It’s turning into a good

night of herping.

Growing up in south Florida, Ron and I were accustomed to roaches, including big ones the size of your thumb.

The sight of them was always accompanied by the shrieks of our mother ― who we came to think of as a sort of

walking cockroach alarm ― followed by the swift, crunchy squish from our father’s shoe.

In the forests of Costa Rica, where roaches are nearly the size of your hand, we revise our definition of “big”

(while hearing the wail of our mother’s cockroach siren going off in our heads).

Herping at night is kind of magical. There’s this sense of being surrounded by living things hidden in the dark,

waiting, watching, moving, and sometimes revealing themselves when a random glance happens to catch them in the

sweep of your headlamp.

During the day you can see animals slowly, a vague image that gradually sharpens into identification, a

suggestive profile or pattern that is confirmed after staring, or a hint of motion that first attracts the eye, then resolves

into recognition.

But at night every find is a surprise, the sudden appearance of something alive in your spotlight. Even the

smallest or most common creatures provide a rush of excitement when silently, unexpectedly, they’re just “there”.

Unlike the frogs, toads, and snakes which are actively awake at night, the lizards we spot are all asleep, lying on

leaves or clinging to trees. One of the prettiest we come across, found once again by Monica the Lizard Queen, is this

large Anole with a striking pattern and an unusually blunt face.

Our final find of the night is barely noticeable because of its small size, a tiny tangle up in a tree. Something on

a distant twig looks slightly out of place to me, so we move closer for a better look, and sure enough, it’s a neonate

Eye-lash Viper knotted on the stem of a leaf.

Eye-lash Viper

Bothriechis schlegelli

The Talamanca highlands of central Costa Rica

Mountain Alligator Lizard

Mesaspis monticola

Red-eyed Tree Frog

Agallychnis callidryus

Serpentarium under construction

Brown Blunt-Headed Snake

Imantodes cenchoa

Casque-Headed Lizard

Corytophanes cristus

Pug-nosed Anole

Norops capito

Slim-fingered Rain Frog (?)

Eleutherodactylus crassidigitus

Wet Forest Toad

Bufo melanochlorus

Brown Blunt-Headed Snake

Imantodes cenchoa