CANADA

May 2016

2 of 2

CANADA

May 2016

2 of 2

Another highway, another sign.

By now I’m detecting a pattern. Apparently it’s Canadian socialism run rampant, ordering oppressed citizens to

“brake for snakes” against their will (at least they say “Please”; in Canada, even tyrants are polite).

But wait, it gets worse. We’re driving on a highway and I notice miles and miles of fencing alongside the road.

Not that unusual, something we see all the time in the States. But this is snake fencing, only a meter high, a permanent

barrier constructed with passages below grade, designed specifically to prevent reptile road mortality.

Jon pulls off the highway and takes a dirt road to our next stop. Even here, more fencing and passages to funnel

snakes and turtles safely to the other side. We step out to take a closer look.

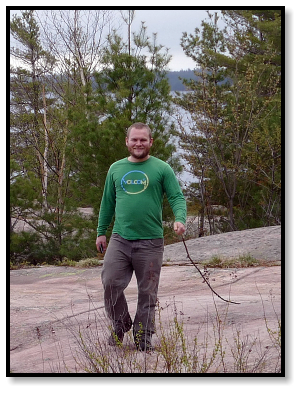

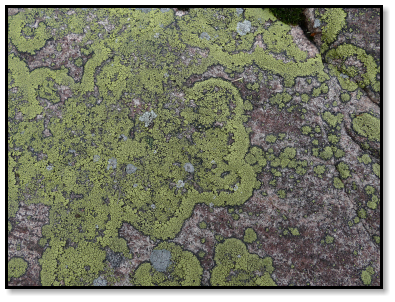

Today Jon and I explore a different kind of rock barrens. Instead of flat alvar pavement, we scramble over

hillsides of gneiss, exposed bedrock of the ancient Canadian Shield.

Too cold this morning for herps, but not for this prickly resident.

We head south for warmer weather, and end up in yet another kind of barrens, a series of rocky ridges with

ponds and wetlands scattered in between.

It’s warmed up nicely, but after an hour of serious searching, not much happening herpwise. A few frogs, some

turtles, but so far, no snakes. We’re reduced to counting invertebrates; Jon brings me a millipede, just for something to

show. “Very nice,” I say politely, not wanting to insult the arthropod. We stand there talking for a few minutes, then

Jon bends over to release the millipede.

BZZZZZZ!! Jon jumps up, totally startled. There’s an angry rattlesnake right in front of us. We were so focused

on the millipede that we never noticed the Massasauga. Probably wouldn’t have if Jon’s movement hadn’t triggered

the alarm. We crack up and congratulate ourselves for being so observant.

We spend another hour hiking around. Jon turns up a juvie milksnake, but that’s about it. We make our way

back to the car and begin the long drive south. Of course, once we’re on the road, we’re confronted by another sign.

Next morning we’re joined by Robert, who further reinforces my stereotype of Canadians: They’re so damned

decent. An experienced herper with many fine stories (flying Fox Snakes included), he’s naturally generous (ditto Jon

et al), and very committed to conservation and social action (I suspect he personally put up all those signs and fences).

Perhaps most significant, Robert makes a really mean chili (OK, that’s not so Canadian).

We begin the day tilting at windmills.

Frustrated in our quixotic efforts to find a Fox Snake, I take comfort in the company of my Canadian companions

(abject apologies for awful alliteration). I’m referring, of course, to Garter Snakes.

It’s a nice surprise when we roll a log and this elegant amphibian makes an unexpected appearance.

En route to another area we come upon a causeway that passes through wetlands. I assume there will be another

snake sign, but I’m unprepared for its grandeur.

This takes it to a whole new level. The entire causeway is lined by fencing and traversed by eco-passages, and on

top of that, they’ve got giant flashing lights to warn approaching motorists. The only thing missing is enforcement by

aircraft. And all this for . . . snakes.

For a country with so few species, Canada has a lot of nerve to do so much for their protection. I mean, it’s

embarrassing to the rest of us. But apparently our friends to the north have a broader attitude towards reptile

conservation. Perhaps all these signs are, well, a sign, that in Canada it’s not just herpers who care about herps.

It’s a revelation, but maybe it shouldn’t be a surprise. At a time when countries all over the world are reacting

with a familiar phobia of those whom they reject, Canadians are lining up to offer their protection. They’re so damned

decent.

Much of Jon’s herping is spent on snake surveys for conservation projects he’s personally initiated. We finish up

in one of his fields where we walked on our first night. I’m hoping for just a few more Garters, to end this trip as it

began, but temperatures are dropping with the dimming light (tomorrow will be snow flurries). I suspect we’ve

already seen our last snakes of the day.

We flip a few boards with no results, and then a lone piece of tin. Simultaneously we all gasp, then roar: we’ve

uncovered a beast.

Throughout the day I’ve been hearing stories about Ontario hogs, snakes as thick your arm, found everywhere

and anywhere. It’s all foreign to my experience. The Hognoses I know from the States are small and uncommon; I’ve

never seen one as massive as the giant before me now.

It’s the final revelation of my first trip to Canada. With such a long cold winter, I’m surprised by the sheer

numbers of snakes that emerge, and now I’m amazed at the size of this Hognose. After all, the farther north, the

smaller the snakes, right? I guess this species makes the most of limited opportunities. Sort of like Canadian herpers.

It’s been an epiphany to experience the inverse devotion at higher latitudes. With such a short season, and so few

species, I might expect half-hearted interest in a hobby that depends so much on warm temps and long life-lists. But I

discover instead a passion for herps equal to any I’ve seen further south, fully invested, and especially admirable given

the constraints of Upper Canada.

Many thanks to all my hosts, with deepest gratitude to Jon for inviting me; organizing the trip; doing the driving;

sharing his expertise; and generously opening his home, his family, and his friends to this stranger from the States.

All text copyright © Eitan Grunwald. All photographs copyright © Eitan or Ron Grunwald

except photographs by others are copyright per photo credits. All rights reserved. Terms

Eastern Hognose Snake

Heterodon platirhinos

Painted Turtle

Chrysemys picta

Blue-spotted Salamander

Ambystoma laterale